8 Solutions

This appendix holds the solutions to selected exercises in the book. Please look at these solutions only after having made a serious attempt at solving the exercises and knowing exactly where you got stuck.

8.1 Continuous-time population models

Von Bertalanffy growth

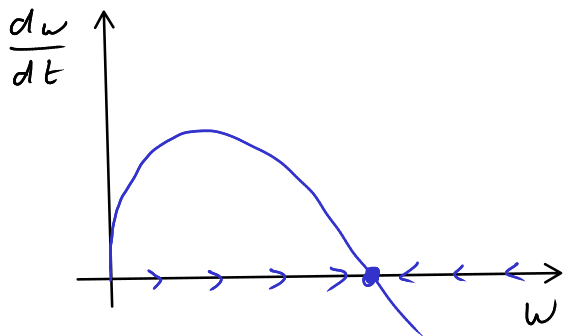

- Seeking a steady state we find \(\alpha w^{2/3}-\beta w = 0\) \(\implies\) \(w^{2/3}(\alpha-\beta w^{1/3})=0\) \(\implies\) \(w=0\) or \(w^{1/3} = \alpha/\beta\). With the graphical approach in Figure 8.1 we see that the non-zero steady state is stable. Hence, \[ \lim_{t \rightarrow \infty} w(t) = \left( \frac{\alpha}{\beta} \right)^{3}. \tag{8.1}\]

For the time derivative of \(u=w^{1/3}\) we find by the chain rule that \[ \frac{du}{dt} = \frac13 w^{-2/3} \frac{dw}{dt} = \frac{1}{3u^2}\left( \alpha w^{2/3}-\beta w \right). \tag{8.2}\] Hence \[ 3\frac{du}{dt} = \frac{1}{u^2}\left( \alpha u^2-\beta u^3 \right) = \alpha-\beta u. \tag{8.3}\] So this change of variables has yielded a linear first-order ODE with constant coefficients, which is easy for us to solve: \[ u(t) = \frac{1}{\beta} \left( \alpha - Ae^{-\beta t/3}\right) \tag{8.4}\] for some integration constant \(A\). If \(u(0)=u_0\) then \(A=\alpha -\beta u_0\).

Translating back to \(w\) with \(w_0=u_0^3\) we finally have \[ w(t) = u(t)^3 = \frac{1}{\beta^3}\left( \alpha - \left( \alpha - \beta w_0^{1/3} \right) e^{-\beta t/3} \right)^3. \tag{8.5}\]

Solving logistic equation

Exercise 1.2: We separate the variables by dividing both sides of the ODE by \(N(1-N/K)\) and multiplying by \(dt\), and then integrate to get \[ \int_{N_0}^{N(t)}\frac{dN}{N\left(1-\frac{N}{K}\right)}=\int_0^t r\,dt. \tag{8.6}\] The right hand side is trivial to integrate, but for the integral on the left-hand side we need to employ the method of partial fractions, using that \[ \frac{dN}{N\left(1-\frac{N}{K}\right)}=\frac{1}{N}+\frac{1}{K-N}. \tag{8.7}\] The left-hand side then gives \[ \begin{split} \int_{N_0}^{N(t)}&\left(\frac{1}{N}+\frac{1}{K-N(t)}\right)dN\\ &=\log N(t)-\log N_0-\log(K-N(t))+\log(K-N_0). \end{split} \tag{8.8}\] We exponentiate both sides to get \[ \frac{N(t)}{N_0}\frac{K-N_0}{K-N(t)}=e^{rt}. \tag{8.9}\] Now we just need to solve for \(N(t)\): \[ N(t)=\frac{N_0Ke^{rt}}{K+N_0(e^{rt}-1)}. \tag{8.10}\]

Harvesting with fixed quota

**Exercise 1.6: If we harvest with a fixed quota \(Q\), the population is described by the equation \[ \frac{dN}{dt} = \alpha N \log\frac{K}{N} - Q. \tag{8.11}\] The subtraction of \(Q\) shifts the graph of the right-hand side down by a distance \(Q\). This brings the non-zero fixed points closer together until \(Q\) is equal to the maximum of the growth rate of the unfished population. If \(Q\) is increased beyond this value the non-zero fixed points disappear and the population will go extinct. is because we are removing \(Q\) individuals from the population at a constant rate. Thus the maximum sustainable yield occurs when \(Q\) equals the maximum replenishment rate of the unfished population. To find that maximum we first solve \[ 0=\frac{d}{dN}\left(\alpha N \log\frac{K}{N}\right)=\alpha\left(\log\frac{K}{N}-1\right). \tag{8.12}\] This tells us that the maximum is at \[ N_{max} = K\,e^{-1}. \tag{8.13}\] Hence the value at the maximum is \[ MSY=Q_{max}=\alpha N_{max} \log\frac{K}{N_{max}}=\alpha\,K\,e^{-1}. \tag{8.14}\] Fishing at this quota is not wise, as this reduces the population to the threshold level below which the population will go extinct.

Wasp model

Exercise 1.7: For \(0\leq t\leq t_c\) the number of workers satisfies \[ \frac{dn}{dt}=r\,n. \tag{8.15}\] Therefore \[ n(t)=n_0e^{r\,t}. \tag{8.16}\]

For \(t_c\leq t\leq T\) the number of reproducers satisfies \[ \frac{dN}{dt}=Rn(t_c)=R\,n_0\,e^{r\,t_c}, \tag{8.17}\] so that \[ N(T)=(T-t_c)R\,e^{r\,t_c}. \tag{8.18}\]

To find the value of \(t_c\) that maximises \(N(T)\) we set the derivative of \(N(T)\) with respect to \(t_c\) to zero: \[ \begin{split} 0&=\frac{d}{dt_c}N(T)=\frac{d}{dt_c}(T-t_c)R\,e^{r\,t_c}\\ &=-R\,e^{r\,t_c}+(T-t_c)R\,r\,e^{r\,t_c}\\ &=R\,e^{r\,t_c}(r\,T-r\,t_c-1). \end{split} \tag{8.19}\] This implies that \[ t_c=T-\frac{1}{r}. \tag{8.20}\]

Wasp model with death

Exercise 1.8: For \(0\leq t\leq t_c\) the number of workers satisfies \[ \frac{dn}{dt}=(r-d)n. \tag{8.21}\] Therefore \[ n(t)=e^{(r-d)t}. \tag{8.22}\] For \(t_c\leq t\leq T\) we have \[ \frac{dn}{dt}=-dn \tag{8.23}\] so that \[ n(t)=n(t_c)e^{-d(t-t_c)}=e^{(r-d)t}e^{-d(t-t_c)}=e^{r\,t_c}e^{-d\,t}. \tag{8.24}\] Also for \(t_c\leq t\leq T\) the number of reproducers satisfies \[ \frac{dN}{dt}=Rn(t)=Re^{r\,t_c}e^{-d\,t}, \tag{8.25}\] so that \[ N(T)=\int_{t_c}^TRe^{r\,t_c}e^{-d\,t}dt = \frac{R}{d}e^{r\,t_c}\left(e^{-d\,t_c}-e^{-d\,T}\right). \tag{8.26}\] To find the value of \(t_c\) that maximises \(N(T)\) we set the derivative of \(N(T)\) with respect to \(t_c\) to zero: \[ \begin{split} 0&=\frac{d}{dt_c}N(T)=\frac{d}{dt_c}\left( \frac{R}{d}e^{r\,t_c}\left(e^{-d\,t_c}-e^{-d\,T}\right)\right)\\ &=Re^{r\,t_c}\left(\left(\frac{r}{d}-1\right)e^{-d\,t_c}-\frac{r}{d}e^{-d\,T}\right). \end{split} \tag{8.27}\] This is equivalent to \[ e^{-d\,t_c}=\frac{1}{1-d/r}e^{-d\,T} \tag{8.28}\] and thus \[ t_c=T+\frac{1}{d}\ln\left(1-\frac{d}{r}\right). \tag{8.29}\]

8.2 Discrete-time population models

Verhulst model

Exercise 2.3: Let’s write the equation as \(N_{t+1}=f(N_t)\) with \[ f(N)=rN\left(1-\frac{N}{K}\right). \tag{8.30}\]

Because \(f(N)\) is positive for all \(N<K\), the only way for \(N_{t+1}\) to be negative is for \(N_t\) to be greater than \(K\). This in turn is only possible if \(f(N_{t-1})>K\). So the function \(f\) at its maximum needs to be larger than \(K\). Because the function describes an upside-down parabola with zeros at \(0\) and \(K\), its maximum is in the middle at \(N=K/2\), where \(f(K/2)=rK/4\). Thus the population can get negative iff \(rK/4>K\), which is equivalent to \(r>4\).

Period-doubling and transcritical bifurcations

We consider the discrete-time model \[N_{t+1}=\frac{rN_t}{1+(N_t/K)^b}=f(N_t)\] where \(r,b\) and \(k\) are positive parameters with \(b>1\).

The steady-state equation is \(f(N^*)=N^*\) which we’ll write as \(f(N^*)-N^*=0\). Substituting in the expression for \(f(N^*)\) and bringing everything on a common denominator gives \[N^*\frac{r-1-(N^*/K)^b}{1+(N^*/K)^b}=0,\] which has the solutions \(N^*=0\) and \(N^*=K(r-1)^{1/b}\). Note that at \(r=1\) these two fixed points coincide, which means there will be a bifurcation there. There are two types of bifurcation where two fixed points meet: in the saddle-node bifurcation (also called tangent bifurcation) the two fixed points annihilate each other, in the transcritical bifurcation they move through each other but exchange their stability. Because the fixed point at \(x=0\) clearly does not disappear in the bifurcation at \(r=1\), we have a transcritical bifurcation.

To determine the stability of the extinction fixed point we calculate the derivative of \(f\) and evaluate at \(0\) which gives \(f'(0)=r\). Because a fixed point is stable if \(|f(N^*)|<1\) we see that the extinction fixed point is stable as long as \(r<1\). At \(r=1\) there is the tangent bifurcation that we already discussed above and for \(r>1\) the extinction fixed point is unstable.

When evaluating \(f'(N^*)\) at the non-zero fixed point it is easier to use that \((N^*/K)^b=r-1\) than to use the expression for \(N^*\) directly. This is a common theme that you also meet in the stability analysis in 2-dim dynamical systems when you evaluate a Jacobian at a fixed point: it saves time to use relationships that are true at the fixed point to simplify expressions. Anyway, the upshot will be that \[f'(N^*)=1-b\frac{r-1}{r}.\] Thus the non-zero fixed point is stable if \(|1-b(r-1)/r|<1\) which means \(1<r<2r/(r-1)\). Hence besides the bifurcation at \(r=1\) there is a bifurcation at \(r=2r/(r-1)\). Because that bifurcation happens when \(f'(N^*)=-1\) we know that it is a period-doubling bifurcation.

8.3 Sex-structured population models

Dominance structure

- The ratio \(F/Q\) in the negative term in the equation for the alpha females represents the fact that if the ratio between the subordinate individuals who gather the food and the alpha females who rely on that food is too small, then the alpha females don’t get enough food and hence are less fit, leading to either a decreased birth rate or an increased mortality rate.

We derive the ODE: \[\begin{split} \frac{d}{dt}\frac{F}{Q }&=\frac{F'Q -FQ'}{Q ^2}\\ &= \frac{(b_F-\mu_F F/Q )F Q-F(b_Q F-\mu_Q Q )}{Q ^2}\\ &=(b_F+\mu_Q )\frac{F}{Q }\left(1-\frac{b_Q +\mu_F}{b_F+\mu_Q }\frac{F}{Q }\right). \end{split} \tag{8.31}\] Ideally you identify this as the logistic equation with initial growth rate \(r\) and carrying capacity \(K\) given by \[ r=b_F+\mu_Q ,~~~K=\frac{b_F+\mu_Q }{b_Q +\mu_F}. \tag{8.32}\] You can then look up the solution in the lecture notes: \[ \frac{F}{Q }(t)=\frac{\frac{F_0}{Q_0}Ke^{rt}}{K+\frac{F_0}{Q_0}\left(e^{rt}-1\right)}. \tag{8.33}\] Otherwise you have to work a bit harder.

Because we have identified \(F/Q (t)\) as the solution of a logistic equation it is easy to see that as \(t\to\infty\), \(F/Q \to K\) with \(K\) as in Eq. 8.32.

We derive the ODE: \[\begin{split} \frac{d}{dt}\frac{F}{M}&=\frac{F'M-FM'}{M^2}\\ &= \frac{(b_F-\mu_F F/Q )FM-F(b_MF-\mu_M M)}{M^2}\\ &=\frac{F}{M}\left(b_F+\mu_M-\mu_F\frac{F}{Q }-b_M\frac{F}{M}\right). \end{split} \tag{8.34}\] We are only interested in the limit of \(F/M\) as \(t\to\infty\). Let us denote this limit by \(R\). We already know that the limit of \(F/Q\) as \(t\to\infty\) is \(K\). The limit of the previous equation gives \[ 0=\frac{d}{dt}R=R\left(b_F+\mu_M-\mu_FK-b_MR\right) \tag{8.35}\] and hence \[ R=\frac{b_F+\mu_M-\mu_FK}{b_M}. \tag{8.36}\] Substituting the expression for \(K\) and bringing everything on a common denominator gives \[ R=\frac{(b_F+\mu_M)(b_Q +\mu_F)-\mu_F(b_F+\mu_Q )}{b_M(b_Q +\mu_F)} \tag{8.37}\] To see that this is always positive we multiply out the numerator: \[ R=\frac{b_Fb_Q +\mu_Mb_Q +\mu_M\mu_F-\mu_F\mu_Q }{b_M(b_Q +\mu_F)} \tag{8.38}\] This is positive because \(b_Fb_Q >\mu_F\mu_Q\)

The birth rates are linear in the number of alpha females and independent of \(M\) and \(Q\). Independence of \(M\) is realistic only if \(M\) is large. Using a weighted mean might be better, i.e., birth rates given by \(b_i FM/(F/n+M)\), where \(n\) is the number of females a male can mate with per mating season. Or we could take into account that the alpha females will reproduce less if there are fewer subordinate individuals gathering food for them, for example by choosing birth rates to be given by \(b_i F Q/(F/n+Q )\), where \(n\) is the number of pregnant females that a subordinate monkey can keep well fed. There are many other possible improvements.

8.4 Age-structured population models

Spotted owl

The given values of the survival probabilities from year to year lead to the following values of the survival probabilities from birth to age \(a\): \[ l_a = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } a = 1, \\ l\, p^{a-2} & \text{if } a \geq 2. \end{cases} \tag{8.39}\]

Substituting these values into the expression for \(\psi(\lambda)\) in Eq. 5.31 gives \[ \begin{split} \psi(\lambda) &= b l \sum_{a=2}^\infty p^{a-2} \lambda^{-a} = lb\lambda^{-2}\sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{p}{\lambda}\\ &= lb\lambda^{-2}\frac{1}{1-\frac{p}{\lambda}} =\frac{lb}{\lambda(\lambda-p)}, \end{split} \tag{8.40}\] where we made use of the formula for a geometric series, valid if \(|p/\lambda|<1\) 1. In particular, the expected number of offspring produced by an individual in their lifetime is \[ \psi(1)=lb/(1-p). \]

If this is greater than \(1\), then the population grows exponentially. If it is less than \(1\), then the population goes extinct.

In this case the Euler-Lotka equation \(\psi(\lambda)=1\) becomes the quadratic equation for \(\lambda\): \[ \psi(\lambda)=\frac{lb}{\lambda(\lambda-p)}=1 \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad \lambda^2 - \lambda p - lb = 0. \tag{8.41}\] The solutions are \[ \lambda_\pm = \frac{p \pm \sqrt{p^2 + 4lb}}{2}. \tag{8.42}\] We are interested in the positive solution \(\lambda_+\). Substituting this value for \(\lambda\) back into Eq. 5.17 and Eq. 5.13 we see that we have found the solution \[ N_{a,t} = \left(\frac{p + \sqrt{p^2 + 4lb}}{2}\right)^{t-a}l_a N_{0,0} \tag{8.43}\] for any choice of \(N_{0,0}\).

Seasonal mortality

Substituting \(n(t,a)=p(t)r(a)\) into Eq. 5.36 and dividing by \(n(t,a)\) gives \[ \frac{p'(t)}{p(t)}+\frac{r'(a)}{r(a)}=-\mu(a)-f(t). \tag{8.44}\] Separating variables gives \[ \frac{p'(t)}{p(t)}+f(t)=-\frac{r'(a)}{r(a)}-\mu(a). \tag{8.45}\] As the left-hand side is independent of \(a\) and the right-hand side is independent of \(t\), both sides must be equal to some constant \(\gamma\). This gives us the two ODEs \[ \frac{d}{dt}\log(p(t))=\gamma-f(t),~~~\frac{d}{da}\log(r(a))=-\gamma-\mu(t). \tag{8.46}\] These have the solutions \[ \begin{split} p(t)&=p(0)\exp\left(\int_0^t\gamma-f(s)\,ds\right),\\ r(a)&=r(0)\exp\left(-\int_0^a\gamma+\mu(s)\,ds\right) \end{split} \tag{8.47}\] Thus the solution for \(n\) is \[ n(t,a)=n(0,0)\exp\left(\int_0^t\gamma-f(s)\,ds\right) \exp\left(-\int_0^a\gamma+\mu(s)\,ds\right). \tag{8.48}\]

Substituting the solution into Eq. 5.37 gives \[ p(t)r(0)=\int_0^\infty b(a)p(t)r(a)\,da. \tag{8.49}\] After dividing by \(p(t)r(0)\) and using our expression for \(r(a)\) from the previous part, \[ 1=\int_0^\infty b(a) \exp\left(-\int_0^a\gamma+\mu(s)ds\right)da =\phi(\gamma). \tag{8.50}\] The factor \(\exp(-\gamma a)\) in the integrand decreases monotonically with increasing \(\gamma\) and therefore so does the integral. Hence the function \(\phi(\gamma)\) is a monotonically decreasing function.

The end of a season occurs at any \(t\in\mathbb{Z}\). At those integer times we can write the integral in the expression for \(p(t)\) as \[ \begin{split} \int_0^t\gamma-f(s)\,ds&=\sum_{i=1}^t\int_{i-1}^{i}\gamma-f(s)\,ds\\ &=\sum_{i=1}^t(\gamma - F)=t(\gamma - F). \end{split} \tag{8.51}\] Hence for the population at the end of the season \(t\) we have \[ n(t,a)=n(0,0)\exp(t(\gamma - F))r(a). \tag{8.52}\] This will go to zero in the limit \(t\to\infty\) if \(\gamma - F<0\). Thus the criterion for extinction is \(\gamma < F\).

Because \(\phi(\gamma)\) decreases with \(\gamma\), \[ \gamma < F \Leftrightarrow \phi(\gamma) > \phi(F). \tag{8.53}\] Because \(\phi(\gamma)=1\), this is equivalent to the condition \(1>\phi(F)\). Thus the condition for extinction is \[ \int_0^\infty b(a) \exp\left(-\int_0^a F+\mu(s)\,ds\right)da <1. \tag{8.54}\]

8.5 Interacting populations

8.6 Epidemics

SIR with recrudescence

Exercise 6.3: The modified equations are \[ \begin{split} \frac{dS}{dt} &= -\beta S I/N,\\ \frac{dI}{dt} &= \beta S I/N - \gamma I + \delta R,\\ \frac{dR}{dt} &= \gamma I - \delta R. \end{split} \tag{8.55}\]

At the steady state all these derivatives have to vanish. From the first equation we find \(S^*=0\) or \(I^*=0\). We are not interested in \(I^*=0\) because we are interested in the endemic state which by definition has \(I^*>0\), so we have \(S^*=0\). The third equation gives \(R^*=\gamma/\delta I^*\). Then \(I^*\) is found from the fact that \(N=S^*+I^*+R^*\) which gives \(I^*=N-\gamma/\delta I^*\). Solving for \(I^*\) gives \[ I^*=\frac{N\delta}{\delta+\gamma}. \tag{8.56}\]

For the stability analysis we reduce the problem to a two-dimensional system by eliminating \(S\) from the last two equations. This gives \[ \begin{split} \frac{dI}{dt} &= \frac{\beta I}{N} \left(N-I-R\right) - \gamma I + \delta R,\\ \frac{dR}{dt} &= \gamma I - \delta R. \end{split} \tag{8.57}\] The Jacobian matrix is \[ A = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{\beta}{N} \left(N-2I-R\right) -\gamma & \delta-\frac{\beta I}{N}\\ \gamma & -\delta \end{pmatrix}. \tag{8.58}\] Evaluated at the endemic state this gives \[ A = \begin{pmatrix} -\frac{\beta}{N}I^* -\gamma & \delta-\frac{\beta}{N}I^*\\ \gamma & -\delta \end{pmatrix}. \tag{8.59}\] This has determinant and trace given by \[ \begin{split} \det(A) &= (\delta+\gamma)\frac{\beta}{N}I^*>0,\\ \text{tr}(A) &= -\frac{\beta}{N}I^* -\gamma -\delta <0. \end{split} \tag{8.60}\] so the endemic state is stable for all positive values of the parameters.

SIR model with reinfections

Exercise 6.4: The modified equations are \[ \begin{split} \frac{dS}{dt} &= -\beta S I/N,\\ \frac{dI}{dt} &= \beta S I/N - \gamma I +\beta\mu R I/N,\\ \frac{dR}{dt} &= \gamma I-\beta\mu R I/N. \end{split} \tag{8.61}\] At the steady state all these derivatives have to vanish. From the first equation we find \(S^*=0\) or \(I^*=0\). We are not interested in \(I^*=0\) because we are interested in the endemic state which by definition has \(I^*>0\), so we have \(S^*=0\). The third equation gives \(R^*=\gamma N/(\beta\mu)\). Then \(I^*\) is found from the fact that \(N=S^*+I^*+R^*\) which gives \[ I^*=N-R^*=N\left(1-\frac{\gamma}{\beta\mu}\right). \tag{8.62}\] This is not the same as the number of infecteds in the endemic state of the model with loss of immunity given in Eq. 6.33.

Sex-structured SIR model

As \(N=S+I+R\) we have \[ \frac{dN}{dt} = \frac{dS}{dt}+\frac{dI}{dt}+\frac{dR}{dt} = -rSI'+rSI'-aI+aI=0. \tag{8.63}\] Hence, \(N\) is a constant. Similarly, \(N'\) is a constant.

We start by deriving an ODE for \(S\) as a function of \(R'\): \[ \frac{dS}{dR'}=\frac{dS}{dt}/ \frac{dR'}{dt} = \frac{-rSI'}{a'I'}=-\frac{r}{a'}S. \tag{8.64}\] This is easy to solve: \[ S(t)=S_0e^{-\frac{r}{a'}R'(t)}. \tag{8.65}\] Similarly, \[ S'(t)=S'_0e^{-\frac{r'}{a}R(t)}. \tag{8.66}\]

At \(t=\infty\) we have \[ S(\infty)=S_0 e^{-\frac{r}{a'}R'(\infty)}. \tag{8.67}\] But at \(t=\infty\), \(I'=0\) and \(N'=S'+I'+R'\) and so \[ S(\infty)=S_0 e^{-\frac{r}{a'}(N'-S'(\infty))}. \tag{8.68}\] Similarly, \[ S'(\infty)=S'_0 e^{-\frac{r'}{a}(N-S(\infty))}. \tag{8.69}\]

8.7 Spatially-structured population models

Travelling wave in 1-species reaction-diffusion model

With \(z=x-ct\) we have \[ \frac{\partial }{\partial t}= \frac{\partial z}{\partial t}\frac{\partial }{\partial z} = -c \frac{\partial }{\partial z} \text{ and } \frac{\partial }{\partial x}= \frac{\partial z}{\partial x}\frac{\partial }{\partial z} = \frac{\partial }{\partial z}. \tag{8.70}\] Substituting this into the PDE gives the ODE \[ -cU' = f(U) + DU''. \tag{8.71}\]

For a travelling wave from left to right (\(c>0\)) we expect solution at \(\pm \infty\) to be at steady state: \(U(-\infty) = 1\) and \(U(\infty)=0\), with \(U'(\pm \infty)=0\).

We will now use a slightly different way to approach the linearisation around the leading edge of the travelling wave than the one we used in the lecture. The methods are equivalent, and it is always instructional to look at different ways of doing the same thing.

At the leading edge of the wave we have that \(U\) is very small, so we can Taylor-expand \(f(U)=f(0)+Uf'(0)+\dots\). We keep only the first two terms and also use that \(f(0)=0\) to get the linear ODE \[ -cU' = Uf'(0)+DU''. \tag{8.72}\] Rather than making an Ansatz for \(U\) as in the lecture, we convert this second order ODE into a set of first-order ODEs by introducing a second variable \(V\) so that \(U'=V\) and \(V' = -\frac{U}{D}f'(0) - \frac{c}{D}V\). In vector notation this reads \[ \begin{pmatrix} U'\\ V' \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1\\ -\frac{f'(0)}{D}U & -\frac{c}{D} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} U\\ V \end{pmatrix}. \tag{8.73}\] The eigenvalues \(\lambda\) of this linear matrix ODE are solutions of \[ \det \begin{pmatrix} -\lambda & 1 \\ -\frac{f'(0)}{D} & -\lambda -\frac{c}{D} \end{pmatrix} = 0 ~~~~\implies ~~~~\lambda^2 + \frac{c}{D} \lambda + \frac{f'(0)}{D}=0. \tag{8.74}\] Real eigenvalues and thus realistic biological solutions exist iff \[ \frac{c^2}{D^2}-4\frac{f'(0)}{D}\geq 0, ~~~~\implies ~~~~ c\geq 2\sqrt{Df'(0)}. \tag{8.75}\]

If \(f(u)= 0\) for all \(u\) we get \(DU''+cU'=0\). Setting \(U(z)=e^{\mu z}\) \(\implies\) \(D\mu^2+c\mu\) \(\implies\) \(\mu = 0\) or \(-c/D\). The general solution is \(U=Ae^{-\frac{c}{D} z}+B\). Clearly \(|U|\rightarrow \infty\) as \(z \rightarrow -\infty\). This is not a biologically realistic solution.

SIR model with logistic growth

One can either approach this systematically or one can just try to guess the necessary change of variables. We will use a blended approach: we guess the expressions for \(u\) and \(v\) by inspecting the equations, and we make a general Ansatz for \(\tilde{t}\).

By comparing the \((1-S/K)\) factor in the equation for \(S\) to the factor \((1-u)\) in the equation for \(u\) we see that \(u=S/K\). It is natural to also choose \(v=I/K\). We write \(\tilde{t}=t/\tau\), where \(\tau\) is still to be determined. With these we have \[\begin{split} \partial_{\tilde{t}}u&=\tau/K\partial_tS= \tau/K\left(rKu(1-u)-\beta K^2uv\right)\\ &= \tau r u(1-u)-\tau \beta K uv \end{split} \tag{8.76}\] By comparing this with equation for \(u\) in the problem statement, we can read off that \[ \tau = \frac{1}{\beta K}, ~~~b=\frac{r}{\beta K}. \tag{8.77}\] Then \[\begin{split} \partial_{\tilde{t}}v&=\tau/K\partial_tI= \tau/K\left(\beta K^2uv-\gamma Kv\right)\\ &=uv-\frac{\gamma}{\beta K}v. \end{split} \tag{8.78}\] By comparing this with the equation for \(v\) in the problem statement we read off that \[ m=\frac{\gamma}{\beta K}. \tag{8.79}\]

By inspection we see that one steady state is \((u(x,t),v(x,t))=(0,0)\) and that another is \[ (u(x,t),v(x,t))=(1,0). \tag{8.80}\] The first describes a situation where the foxes are extinct, the second the situation where in the absence of the disease the fox population sits at its carrying capacity. We look for another steady state \((u(x,t),v(x,t))=(u^*,v^*)\) with \(v^*\neq 0\). From the equation for \(v\) we read off that \(u^*=m\) and then from the equation for \(u\) we get \(v^*=b(1-m)\). This is the endemic state because the number of infecteds is non-zero. It exists as long as \(m<1\). This tells us that the existence of the endemic state is independent of the intrinsic growth rate \(r\) of the fox population but does depend on its carrying capacity.

We know from part a. that \(\partial_{\tilde t}u=\partial_t S/(\beta K^2)\). Thus we now want \(D_1\partial_x^2 S/(\beta K^2)=\partial_{\tilde{x}}^2 u\), where \(u=S/K\). Hence \[ \tilde{x}=\sqrt{\frac{K\beta}{D_1}}x. \tag{8.81}\] Then \(d\,\partial_{\tilde{x}}^2v =d\,D_1\partial_x^2I\) but we want \(D_2\partial_x^2I\) so we need \[ d=\frac{D_2}{D_1}. \tag{8.82}\]

Substituting the wave Ansatz into the PDEs for \(u\) and \(v\) gives \[\begin{split} -cA'&=bA(1-A)-AB+A''\\ -cB'&=AB-mB+dB''. \end{split} \tag{8.83}\]

If \(A(\infty)=1\) (which corresponds to \(S=K\)) then that means that at \(x=\infty\) the system is in the disease-free state and thus \(B(\infty)=0\). At \(x=-\infty\) the system must thus be in the endemic state, so \(A(-\infty)=u^*=m\) and \(B(-\infty)=v^*=b(1-m)\). So the key to this question was the observation that the travelling wave will always have to interpolate between two steady states. Furthermore, it is the stable steady state that will invade the unsteady stable state. In this case, this means that the stable endemic state on the left invades the unstable disease-free state on the right, so we have a right-moving wave.

At the leading edge where \(B\) is very small, \(A\) is very close to \(1\), so \(A=1-\epsilon\) for a small \(\epsilon>0\). The equations Eq. 8.83 can thus be approximated by the linear equations \[ c\epsilon'=b\epsilon-B-\epsilon'',~~~-cB'=B-mB+dB''. \tag{8.84}\] We obtained this by dropping all terms involving \(\epsilon^2\) or \(\epsilon B\) because they are negligible when \(\epsilon\) and \(B\) are both small.

We concentrate on the second equation, which we solve with the Ansatz \(B(x)=\exp(\lambda x)\), where we need \(\lambda\) to be real and negative to match the shape of \(B\) at the leading edge. Substituting this Ansatz into the equation gives the characteristic equation for \(\lambda\): \[ d\lambda^2+c\lambda+1-m=0, \tag{8.85}\] and thus \[ \lambda=\frac{-c\pm\sqrt{c^2-4d(1-m)}}{2d}. \tag{8.86}\] Because we know that \(\lambda\) is real and negative, we need deduce that \(c\) is positive and \[ c\geq 2\sqrt{d(1-m)}. \tag{8.87}\] That \(c\) is positive confirms our earlier deduction that the wave should be a right-moving wave.

Derive Turing instability

Here, \[ f(u,v)=a-u + u^2v, ~~~~ g(u,v)=b-u^2v. \tag{8.88}\]

Step 1. Uniform steady state

\[ a-u^* + {u^*}^2 v^*=0~\text{ and }~b-{u^*}^2 v^*=0 \tag{8.89}\] implies \[ (u^*,~v^*)=(a+b,~b/(a+b)^2). \tag{8.90}\]

Step 2. Linearise

Set \(u=u^*+\xi\) and \(v=v^*+\eta\) with \(\xi\) and \(\eta\) small. Substitute and Taylor expand to get \[ \begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial \xi}{\partial t} \\ \frac{\partial \eta}{\partial t} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} \\a_{21} & a_{22} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \xi \\ \eta \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} D_1 \frac{\partial^2 \xi}{\partial x^2} \\ D_2\frac{\partial^2 \eta}{\partial x^2} \end{pmatrix}, \tag{8.91}\] where \[ \begin{split} a_{11} = \frac{\partial f}{\partial u}(u^*,v^*) &= -1+2u^*v^* \\ &= -1+2(a+b)b/(a+b)^2 \\ &=(b-a)/(a+b)\\ a_{12} = \frac{\partial f}{\partial v}(u^*,v^*) &= {u^*}^2 =(a+b)^2\\ a_{21} = \frac{\partial g}{\partial u}(u^*,v^*) &= -2 u^* v^* =-2b/(a+b)\\ a_{22} = \frac{\partial g}{\partial v}(u^*,v^*) &= -{u^*}^2 =-(a+b)^2 \end{split} \tag{8.92}\]

Step 3. Solutions

Make the Ansatz \(\xi = A_1 e^{\sigma t} \sin( kx+\alpha)\) and \(\eta = A_2 e^{\sigma t} \sin( kx+\alpha)\). Substitute to get \[ \begin{pmatrix} \sigma - \frac{b-a}{a+b} +D_1k^2 & -(a+b)^2 \\ \frac{2b}{a+b} & \sigma + (a+b)^2 +D_2k^2 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} A_1 \\ A_2 \end{pmatrix}= {\mathbf 0} \tag{8.93}\] For a non-trivial solution we require the determinant of this matrix to be zero (otherwise we would be able to find an inverse, etc.). Hence, \[ \sigma^2 + \left[ (a+b)^2 - \frac{b-a}{a+b} + (D_1+D_2)k^2 \right] \sigma + h(k^2) = 0, \tag{8.94}\] where \[ h(k^2)= D_1D_2k^4 - \left[ D_2\frac{b-a}{a+b} - D_1(a+b)^2 \right] k^2 +(a+b)^2. \tag{8.95}\]

Step 4. In the absence of diffusion (Put \(D_1=0=D_2\).) \[ \sigma^2 + \left[ (a+b)^2 - \frac{b-a}{a+b} \right] \sigma + (a+b)^2 = 0. \tag{8.96}\] For \(\sigma\) to have roots in the left half of the complex plane (giving us a stable steady state) we need \((a+b)^2-\frac{b-a}{a+b}>0 ~\implies ~ b-a<(a+b)^3\) and \((a+b)^2>0\) (which it is).

Step 5. With diffusion (\(D_1\neq 0\neq D_2\).)

We want steady state to be unstable in this case. The coefficient of \(\sigma\) is \[ (a+b)^2 - \frac{b-a}{a+b} + (D_1+D_2)k^2 > (D_1+D_2)k^2>0 ~~~~\mbox{from Step 4} \tag{8.97}\] Therefore, we require \(h(k^2)<0\) for some \(k^2\) for there to be an instability.

As \(h(0)>0\) we must have two positive real roots of \(h(k^2)=0\) for there to be an instability.

Real distinct roots (\(\implies ~~B^2-4AC>0\)) \[ \implies \left[ D_2\frac{b-a}{a+b} - D_1(a+b)^2 \right]^2> 4D_1D_2 (a+b)^2. \tag{8.98}\] Both positive (\(\implies B<0\)) \[ \implies D_2\frac{b-a}{a+b} - D_1(a+b)^2 > 0. \tag{8.99}\]

If \(\lambda\geq p\), then \(\psi(\lambda)\) diverges and does not satisfy the Euler-Lotka equation \(\psi(\lambda)=1\).↩︎